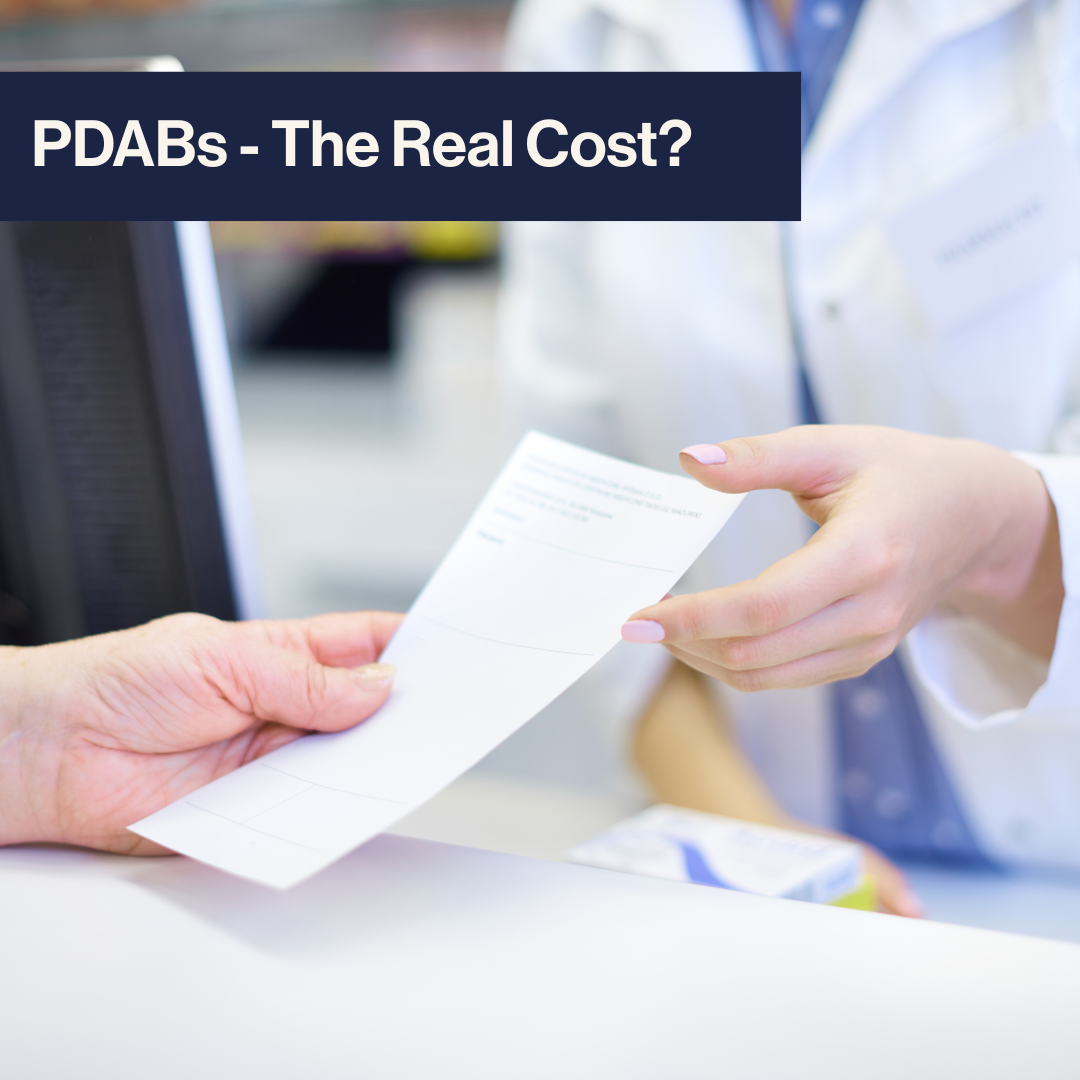

On March 24, 2025, Virginia Governor Glenn Youngkin vetoed House Bill 1724, effectively halting legislation that would have created a Prescription Drug Affordability Board (PDAB) in the state. In a statement, Governor Youngkin said that establishing a PDAB would “limit access to treatments and hinder medical innovation, especially for life-threatening or rare diseases.” This is the second consecutive legislative session in which the Governor has blocked efforts to establish a PDAB in Virginia. What’s driving the renewed push for this policy, and why are some patient advocates applauding the Governor’s decision to reject it? For this edition of Policy Corner, we’ll explore PDABs, why patient advocacy organizations like the Infusion Access Foundation find them deeply concerning, and potential solutions to patient drug costs.

What are PDABs?

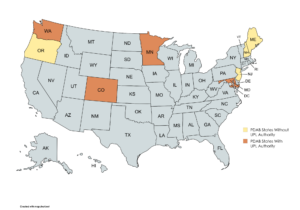

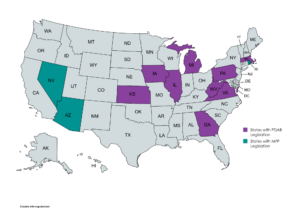

For those unfamiliar, Prescription Drug Affordability Boards (PDABs) are oversight entities established by state governments tasked with reviewing high-cost prescription drugs and assessing whether these drugs create affordability challenges for patients or strain state healthcare programs. While their structure and scope of authority differ across states, PDABs typically share several core functions and characteristics. These boards are often composed of appointed experts in healthcare, economics, and, occasionally, patients and providers. In some states, PDABs are authorized to establish upper payment limits (UPLs), which serve as price ceilings on certain expensive drugs, effectively capping reimbursement to providers. Currently, eight states (Colorado, Maine, Maryland, Minnesota, New Hampshire, New Jersey, Oregon, and Washington) have active PDABs; four (Colorado, Maryland, Minnesota, and Washington) have the authority to establish UPLs.

What’s so bad about PDABs?

This all sounds great, right? It’s complicated. While PDABs are often presented as a solution to rising drug costs, the Infusion Access Foundation and the patient advocacy community have raised concerns about the unintended consequences of this form of government-imposed price-setting mechanism. At the core of this issue is the question, “What does ‘affordability’ truly mean?”

Regarding PDABs, this concept of “affordability” is often framed regarding cost savings for health plans and state budgets, with far less consideration given to patient access or provider sustainability. Consider infusion centers as an example. These providers operate under a “buy-and-bill” model, meaning they must purchase medications upfront and seek reimbursement from health plans after administering treatment. If a PDAB sets a UPL below the actual acquisition cost of a drug, providers are left to absorb the financial loss with each dose they deliver. In the best-case scenario, this may lead infusion centers to stop offering medications subject to UPLs to stay afloat; in the worst-case scenario, ongoing losses could trigger clinic closures or service reductions, making it harder for patients to access critical treatments. In either outcome, patients lose access to care, even as the PDAB points to reduced drug prices as a success.

UPLs don’t just influence the drugs they directly apply to: they can have a ripple effect across the broader medication space. For example, if Drug X is subject to a UPL and Drug Y, a more expensive alternative, is not, health plans are incentivized to promote the use of Drug X to minimize costs. To discourage the use of Drug Y, health plans often employ “utilization management” strategies that can be unsafe for patients and create administrative barriers for providers. These strategies include step therapy, where patients must try and fail on a cheaper drug before accessing the one prescribed by their doctor, and non-medical switching, where a health plan overrides a provider’s recommendation and switches a patient between drugs for non-clinical reasons. Because covering Drug Y would cost more, health plans may escalate these barriers, making it increasingly difficult for patients to access it. Combined with the provider sustainability issue outlined previously, you can see how setting a UPL for one drug can impact patient access for multiple other drugs, compounding the problem further.

A recent report from the Partnership to Fight Chronic Disease surveyed health plans with experience in potential PDAB-regulated markets. Key findings from the report include:

- 77% of surveyed health plans believe UPLs would disrupt patient access to prescription drugs due to changes in coverage, tiering adjustments, increased cost-sharing, or supply chain complications.

- 50% predict increased utilization management restrictions, including step therapy and non-medical switching.

The report reinforces the Infusion Access Foundation’s concerns that UPLs will lead to higher patient costs and reduced access to critical treatments. Despite the concerns raised by patient and provider groups, legislative momentum around PDABs continues to grow. Aside from Virginia, lawmakers in eight states (Georgia, Illinois, Iowa, Kansas, Massachusetts, Michigan, Pennsylvania, and West Virginia) have introduced bills to create their PDABs, some with the authority to set UPLs. Meanwhile, three states (Arizona, Nevada, and Rhode Island) have introduced bills setting drug prices at the Maximum Fair Price (MFP) outlined by the federal Medicare Drug Price Negotiation Program (MDPNP), which can be thought of as essentially a UPL for the Medicare program.

What can we do?

Fortunately, there are several alternatives to UPLs that PDABs can consider to improve patient affordability more effectively.

One such approach is to rein in the practices of pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs), third-party entities hired by health plans to administer prescription drug benefits. PBMs typically negotiate rebates with drug manufacturers in exchange for favorable placement on a health plan’s formulary, the list of drugs covered for enrollees. However, PBMs often retain a percentage of these rebates as a fee, creating a perverse incentive to prioritize higher-cost drugs with more significant rebate potential. This dynamic, in turn, puts pressure on manufacturers to factor in the rebate in a drug’s list price to ensure competitive placement. Two potential solutions to realign these incentives include requiring PBMs to pass through 100% of negotiated rebates to patients, or “delinking” PBM compensation from a drug’s list price. Both reforms could help lower costs while improving transparency and accountability.

Prohibiting health plan programs known as copay accumulators and maximizers is another solution to rising patient drug costs. A copay accumulator program is a policy implemented by an insurance company that allows a health plan to collect a patient’s copay assistance but does not count the assistance toward the patient’s deductible or out-of-pocket maximum. A copay maximizer program is a similar policy. Still, the maximum value of the copay assistance is evenly applied throughout the patient’s plan year, preventing the patient from reaching their deductible or out-of-pocket maximum that would require health plans to cover the rest of their costs. Each of these programs directly impacts the actual costs of drugs for patients and is ripe for reform. The “All Copays Count” movement has made great strides, enacting legislation banning these programs in nearly half of the US states.

A final, more systemic solution involves reforming utilization management by health plans, which is often a barrier to timely, appropriate care. Practices such as step therapy and non-medical switching can interfere with physician-recommended treatment plans, particularly for patients managing chronic conditions that require infusion therapies. When patients are forced to try and fail on treatments preferred by a health plan, the result can be disease flare-ups, avoidable hospitalizations, and ultimately higher costs across the healthcare system.

Tackling high drug costs is essential, but we must be careful not to solve one problem by creating others. PDABs might sound like a smart fix on paper, but when they set price caps without thinking through the ripple effects, patients and providers can end up paying the price. Instead of leaning on one-size-fits-all limits, there are better ways to make medications more affordable, like holding PBMs and health plans accountable and ensuring patient support helps patients. We need solutions that protect access and lower costs to improve healthcare for everyone.